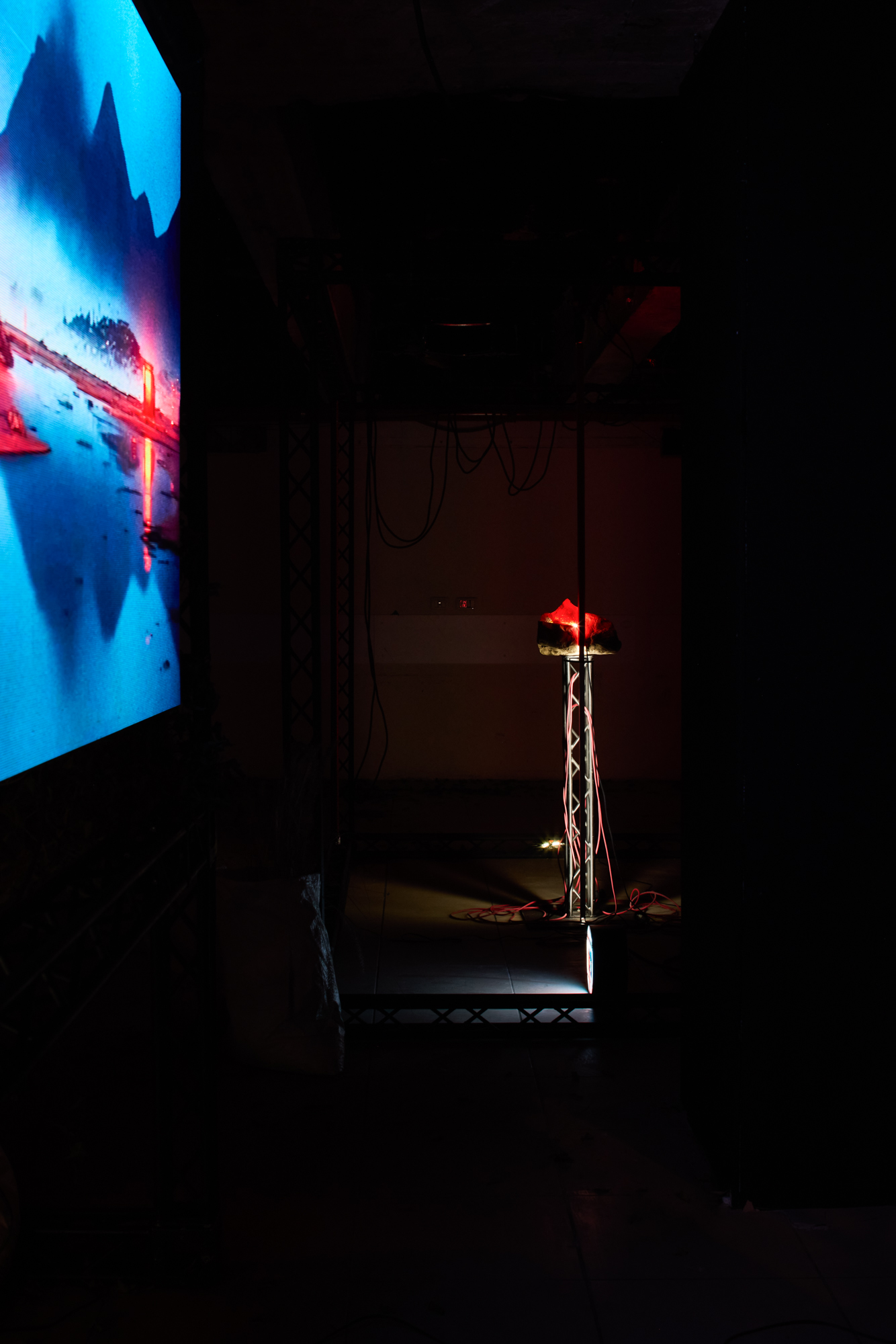

At Hamivne, Ahad Haam 11, Tel Aviv

Ancient AI proposes an alternative view of artificial intelligence: not as an abstract, virtual, or “immaterial” entity, but as the direct outcome of ancient matter—geological, mineral, terrestrial. What appears to be a transparent, clean technological system—“algorithm,” “cloud,” “model”—is in fact grounded in raw physical foundations: rare earth minerals, metals, layers of rock, and slow geological time. The point of departure of the work is this understanding: that the technological fantasies of our time remain deeply dependent on earthly, primitive, timeless materials.

The installation was realized in a former bank vault beneath Migdal Shalom Meir in Tel Aviv—an architectural remnant of financial systems built to secure, store, and protect value. This subterranean space, historically designed to safeguard capital, becomes a resonant container for a work concerned with the material foundations of contemporary technological economies. Just as financial power once depended on gold reserves and physical assets locked underground, today’s digital infrastructures and artificial intelligence systems rely on hidden geological extractions, mineral dependencies, and global supply chains buried out of sight. The vault thus operates not merely as a site, but as a conceptual extension of the work: a space where value, matter, and control converge.

From the Ground to the Algorithm

The installation traces the paths of minerals through six extraction and processing sites—five in China and one in the United States. These are not merely “locations,” but friction points where geology, power, technology, and environmental damage converge into a single physical source from which artificial intelligence emerges. The floor of the installation is inlaid with natural red quartz, mined in Brazil and India—real, ancient minerals that carry compressed geological time within them. Their presence is neither image nor simulation, but material fact: a radiating physical testimony to the beauty and violence of extraction and to the direct contact between technology and the ground.

Lithium, cobalt, neodymium, and cerium—these are the materials from which servers, screens, and AI infrastructures shaping our lives are built. Their extraction involves energy-intensive, polluting, and violent processes of mining, separation, and refinement. The toxic pink lakes and fluorescent flamingos are not merely represented; they are materially produced by the very mining processes they appear to mourn.

The choice of these sites underscores the deep dependence of Western technological economies on Chinese supply chains, alongside American attempts to rebuild mineral independence. AI is thus presented not only as an idea, but as the product of an active geopolitical struggle over the foundational materials of the digital age.

Reverse Movement

Ancient AI constructs a movement opposite to the one we are accustomed to: not from code to image, but from earth to technology; not from cloud to screen, but from mineral to digital fantasy. It is a trajectory in which matter precedes image, and geology precedes intelligence.

The work presents a condition in which environmental destruction and technological aspiration are not opposites, but two sides of the same process. The growing dependence on rare minerals and continuous extraction reveals technological stability as an illusion. The entire system exists only as long as the earth continues to yield.

The human no longer stands at the top of a technological pyramid, but becomes one layer within a broader network of dependency—between matter, energy, machine, and consciousness. The “new nature” that emerges here is simultaneously a bounty, a warning, and a glimpse of a future uncomfortably close—a future shaped by an intensifying desire for rare minerals and infinite computation.

Hidden Structure

Within the context of an exhibition concerned with the notion of “structure,” Ancient AI seeks to examine the hidden structure of artificial intelligence: not as an abstract system of code and algorithms, but as a physical, material, and geological structure. By dismantling technology into its most fundamental layers, the work offers a critical reading of concealed structures—structures of power, resource dependency, and natural history embedded within every chip.

Through a romanticism of future ruins, the installation explores a hybrid, post-natural condition. This is a world in which nature is no longer “nature” in its traditional sense, but the product of damage, engineering, technology, and simulation. The landscape becomes a symbol of a reality in which technology does not hover above the world, but draws from it, shapes it, and exhausts it.

The Swan and the Obelisk: The Symbolic Language of Ancient AI

Within this landscape, the swan, the flamingo, and the red obelisks appear as central images. These are not stable symbols, but fluid and contradictory figures, operating as axes of tension between beauty and threat, order and rupture, nature and technology.

The swan is among the richest symbols in human culture. Throughout history it embodies a deep duality: purity and violence, elegance and latent power. Its appearance suggests harmony, yet its behavior reveals territoriality and aggression—beauty that is not innocent.

In various mythologies, the swan appears as a creature of transformation: Zeus disguising himself as a swan, swan maidens who shift form, and The Ugly Duckling as a story of rebirth and self-discovery. Its movement between water, land, and sky marks it as a symbol of passage between states of being, of cognitive migration and mediation between realms. The tension between the white swan and the black swan sharpens this duality: order versus disruption, harmony versus anomaly. In Ancient AI, the swan appears as a post-natural creature—testimony to a world in which the boundaries between nature, technology, and image have collapsed.

The flamingo is a species capable of surviving extreme environments: saline, alkaline, toxic lakes. In Ancient AI, the flamingo appears as a post-natural organism—not a wild animal in the classical sense, but a life form reshaped by industrial chemistry, mining, and the residues of human processes. In biology this is a superpower; in the work it becomes a dangerous analogy. It depicts a world in which life does not vanish, but adapts to damage. Adaptation is not a solution, but the normalization of catastrophe. Like AI systems, the flamingo “functions” efficiently within destructive conditions it did not choose.

The red obelisks are positioned as hybrid monuments—between industrial remnants and ritual structures. They mark sites of extraction and injury to the earth, their red glow suggesting heat, energy, and alarm. Like ancient obelisks, they carry a monumental aura, yet their language is synthetic, neon, and industrial, implying that the temples of the future are infrastructural.

The repetition of the obelisks across the landscape creates a sense of a network: nodes of distributed non-human consciousness, data pillars, or transmitters that may continue to operate even after the collapse of the human system. At the same time, they function as ecological alarm columns—indicators of ongoing environmental harm and silent witnesses to a slow catastrophe.

Together, the swans, flamingos, and obelisks form a post-natural mythology: a visual language in which beauty and threat are inseparably intertwined, and the algorithmic image is revealed as dependent on matter violently extracted from the earth. Nature does not disappear—it mutates, distorts, and re-emerges as a charged symbol of the technological age.

Curated by Sivan Sebbag Zelensky. Artist management: Ariel Kotzer. Sponsored by Hamivne Group. Photos by Harel Gilboa